In our research, we examine discourses that shape the strategies and resource allocation processes of organizations in the philanthropic and development sectors. Discourses often become fads with surprisingly long tails. Discourses around innovation and disruption, business model innovations, scaling, big-bet philanthropy, system change, and system transformation are sustained by leaders and organizations with the ambition to create more and faster social impact. Recently, we examined the trajectory of the discourse around “Grand Challenges”, introduced in 2003 by Bill Gates to frame an ambitious effort by his foundation to tackle some of the world’s toughest social problems. But the realities of social problems often prove resilient to inspiring discourses. Ten years later, having spent a billion dollars, Gates admitted that they had achieved little and that he has been slightly naïve about this Grand Challenges effort.

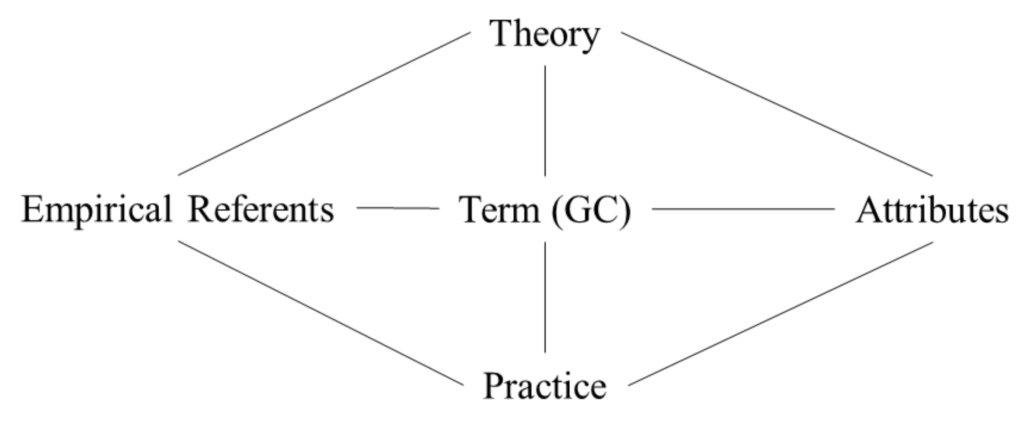

We are concerned about the ambiguity of the central terms that define discourses in the philanthropic and development sectors and the lack of scrutiny investigating the effectiveness of decisions based on them. Only a few years after the Bill & Melinda Gates foundations’ adoption of the term Grand Challenges (GC), management scholars started to introduce the term to spark interest in research on societal challenges. The term appeared more and more frequently at management conferences, in research articles, calls for special journal issues, and in workshops for PhD students. An array of articles published in the first years after adopting this term signaled real momentum and potential. But even a superficial engagement with this literature left us puzzled about the diversity of definitions of GC in terms of conceptual attributes and associated empirical referents. We wondered: Can management research on GC achieve its clearly articulated ambitions of theory development and informing practice that addresses important societal challenges? Together with our coauthor Charlotte Traeger from the University of Bern, we evaluated the first decade of GC management research for signs of conceptual development of the term GC, for consistency of attributes, for boundary criteria that define empirical membership of phenomena (empirical referents), and for signs of theory development and concrete implications for practice (Figure 1).

Concepts and theoretical claims about referred phenomena are essential enablers of a progressive science within a community of scholars. We found many GC articles that individually were exciting and interesting. But like pieces of a larger GC puzzle we struggled to see how they might fit together into a meaningful whole. The breadth of empirical referents and attributes associated with GC grew dramatically over this first decade of management research. Authors used the term GC in different and inconsistent ways. Many did not even define the term or provide any rationale for using this term in a research article. Editors and reviewers seemed to tolerate these inconsistencies. Some influential editors welcome the expansion of empirical referents of GC (and the concomitant expansion of attributes). Consequently, we have created a hodge-podge of GC research with no transparent criteria for evaluation or for deciding whether and in which way GC research might eventually be successful. Without more explicit conceptual development, GC research may become caught up in an endless language game that fuels unconnected studies of allegedly interesting and important GC phenomena. We also worry that knowledge claims may be insufficiently contextualized to inform practice.

The lack of serious efforts towards developing the analytical potential of GC prompted us to recommend an alternative route for GC research. Instead of employing GC as a concept for theory development, we suggest rejuvenating the perspective on GC as defining a set of research principles. This perspective was proposed by early editorials in leading management journals that helped kick-start the wave of GC research. Keeping the term GC to frame a collective research effort maintains the positive momentum and excitement that defined the first decade of GC research. But the focus of GC research would shift to how we go about studying important societal scholars. Applying a set of clearly articulated principles for GC research would enable us to address long-standing criticisms of management research such as being multi-paradigmatic and thus pre-scientific because scholars grounded in different research principles cannot or do not want to understand and engage with each other. A lack of consensus on research principles in management scholarship is reflected in debates and numerous editorial essays on what a theory is, how to accumulate knowledge, and whether research is relevant for society. To make progress, we will need to get these critical voices out of the editorial essay parking lot and enact them in research practice.

Early editorials that promoted GC research suggested urgency and broadening our theoretical and empirical scope as core principles for GC research. But these three principles alone do not shield us from incommensurable, multi-paradigmatic research efforts hampering theoretical development and practical usefulness. We therefore added a fourth principle, realism, as a metatheory for practice-oriented theorizing. The principle of urgency signals a moral imperative that we act to guide business leaders, employees, and stakeholders with systematic, unbiased, and empirically robust evidence on mechanisms with which to tackle important social problems. Living up to this principle, for example, requires that we stop proposing calls for special issues on GC that only promote uncoordinated research aligned by an ambiguous term. Broadening the theoretical scope encourages management scholars to explore other fields and disciplines to expand the repertoire of mechanisms considered in GC research. This exploration would help to specify the concrete obstacles for a given GC, increase the explanatory depth of phenomena, and inform practical interventions. Broadening the empirical scope of GC research does not necessarily mean broadening the variety of considered phenomena. It means penetrating the empirical layers of societal problems more deeply by engaging closely with relevant stakeholders and carefully considering how to translate complex social context into concrete phenomena for investigation. Finally, we propose to adopt scientific realism and its ontological commitments and epistemological principles as an effective metatheory for theorizing managerial efforts in complex settings. Realism can help integrate and overcome the limitations of positivist and relativist positions and legitimize effective forms of engaged and activist scholarship. Realism ideally supports cumulative GC research by validating theories in terms of their practical adequacy. Adopting this principle counteracts tendencies to limit practical implications of research to a sidenote in the discussion section of articles and promotes actionability – the expectation of specific effects of contextual action – to an arbiter of the truth value of our knowledge claims.

We are hopeful that the second decade of GC research will be marked by ambitious advances in both theory and practice. At the same time, we recognize that to getting there it will take a shared willingness to revisit and to productively debate some of the most fundamental rules of how management research is conducted.

Additional Information on the authors

*Christian Seelos

Christian Seelos is a Distinguished Fellow and Director of the Global Innovation for Impact Lab at the Stanford University Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society. Previously, he held posts at the Harvard Kennedy School, at the Skoll Center for Social Entrepreneurship, the KU Leuven, as well as at IESE Business School.

Christian’s research on innovative business models in the context of deep poverty was recognized by the Strategic Management Society (Best Paper Award for Practice Implications, 2007). He won several awards, including the Gold Price of the IFC-FT research competition on private sector development and the Terry McAdam book prize for “the most inspirational and useful new book contributing to nonprofit management“.

Christian is widely published in peer-reviewed journals in the natural- and social-sciences as well as in various practice- and news-oriented formats.

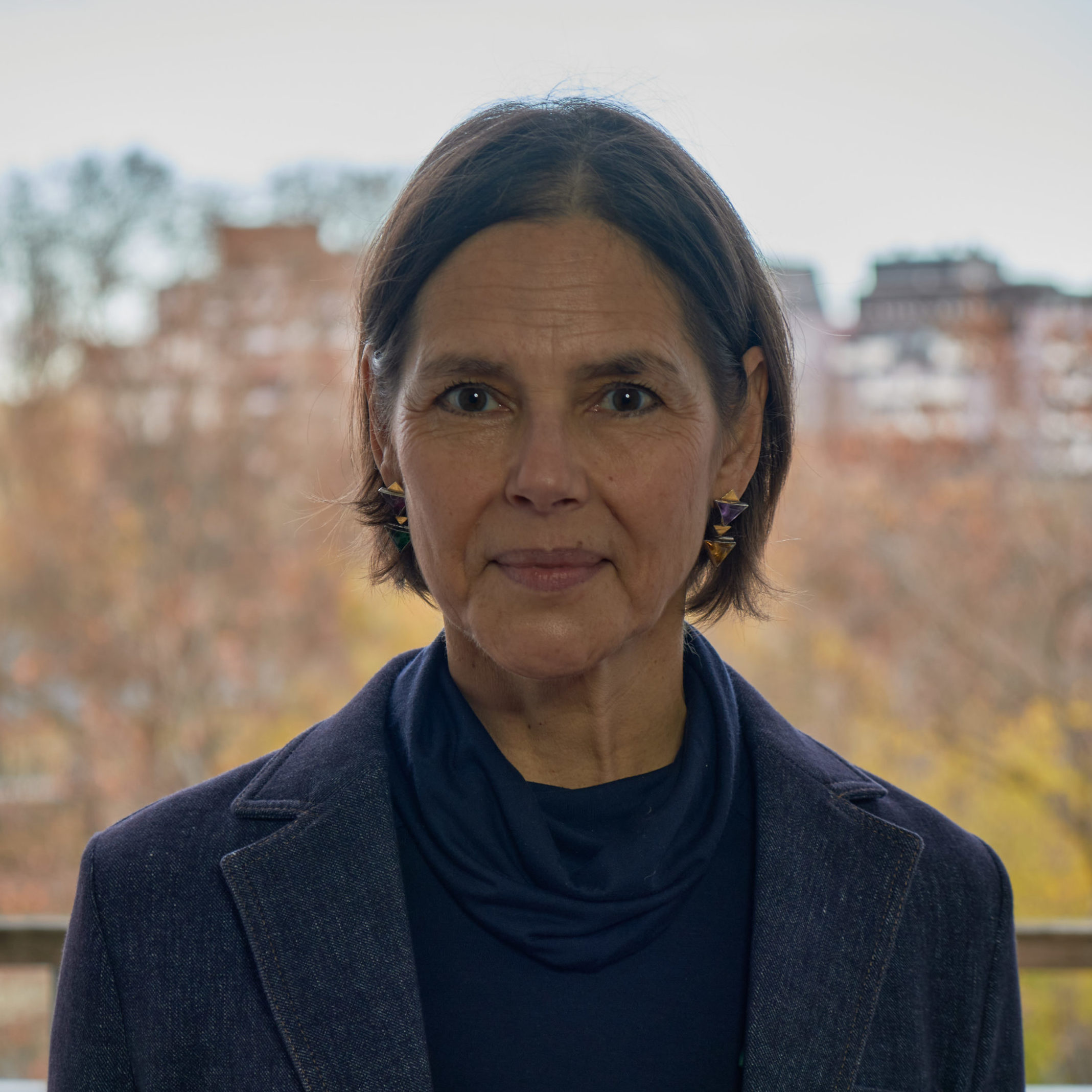

** Johanna Mair

Johanna Mair is a Professor of Organization, Strategy and Leadership at the Hertie School in Berlin. Her research focuses on the nexus of organizations, institutions, and societal challenges. Her recent work centers on mechanisms that enable organizations to transform social systems and make progress on social problems. She is the academic editor of Stanford Social Innovation Review and co-directs the Global Innovation for Impact Lab at the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society.

Her book Innovation and Scaling – How effective Social Entrepreneurs create Impact (Stanford University Press, 2017) co-authored with Christian Seelos has won the 2017 Terry McAdam Award at ARNOVA and the 2018 ONE Outstanding Book Award at the Academy of Management Meeting. Her research has been published widely including the Academy of Management Journal, Journal of Business Ethics and Nature Human Behavior.

Suggested citation

Seelos, Christian and Mair, Johanna (2023): “The Future of Grand Challenges Research: Retiring a Hopeful Concept and Endorsing Research Principles”, Grand Challenges Blog @ HEC Lausanne, Université de Lausanne, March 2023

-

Christian Seelos

Christian Seelos is a Distinguished Fellow and Director of the Global Innovation for Impact Lab at the Stanford University Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society.

View all posts -

Johanna Mair

Johanna Mair is a Professor of Organization, Strategy and Leadership at the Hertie School in Berlin.

View all posts

One Response

some technical terms are not well explained, which might make it difficult for general readers to fully grasp the content

Visit us Teknologi Telekomunikasi