The world is not in a good shape. When Rockström and colleagues defined the ecological crisis along nine different planetary boundaries – from global warming to the extinction of species in 2009, they did not expect that six out of these nine boundaries would be transgressed just one decade later. Ecological problems increasingly destabilize societies, reinforcing existing and creating new social problems. Permacrisis, understood as an “extended period of insecurity and instability” was the word of the year in 2022 according to the Collins English Dictionary. Given the enormous and urgent challenges humanity is facing, there can be no doubt that academia has to play an essential role in providing solutions and answers.

While scientists might agree on the urgency of our multiple crises, it does not necessarily lead them to reorient their own energy toward them. While in natural sciences, scholars increasingly devote their interests and energy to the numerous aspects of grand challenges, skimming through the journals of scholars in management and economics, one does not get the impression that the urgency of the problems is translating into a shift in social sciences as well. Our system of knowledge production is increasingly dysfunctional from a societal perspective and one of the reasons might be the incentive mechanism of the academic world.

Problems with the traditional academic incentive structure

The traditional academic incentive structure makes it difficult to engage with grand challenges. Just to highlight some of the aspects of this problem:

- Quantity over quality. Scholars are incentivized to publish as many articles in top journals as possible. One big research question is thus often split into several albeit smaller projects that zoom into ever smaller details. In a game that rewards quantity, more papers in top journals that lead to more citations is the strategy that first leads to tenure and then to reputation. It is self-referentially closed and not connected to problems in the world.

- Facts over values. Operating from within a positivist epistemology, many scientists naively believe in a separation of facts and values, assuming that what they do is only “finding” those objective causal links that explain and predict phenomena. Normative evaluations are considered to be outside of their profession. In reality, however, any research is operating with a normative foundation (markets must be free, choices must maximize utility, property rights need to be protected, growth is good, etc). Grand challenges come with normative conclusions about the need for changes in the system. Many scientists do not want to engage in such discussions. They do not want to be seen as “activists”.

- Analytical over holistic perspective. Grand challenges are complex and often require a holistic perspective that investigates how multiple phenomena relate. Social scientists prefer to clean the investigation of a phenomenon from as much “noise” as possible to find robust causal relations. This analytical approach stands in the century-old tradition of the enlightenment that builds on the assumption that we acquire knowledge by drilling into ever deeper details, deconstructing the whole, and later aggregating the details to understand the whole.

- Siloed fields over transdisciplinary discourses. Research on Grand Challenges is in large parts transdisciplinary. It might for instance require an analysis across discussions in biology, psychology, and management. Being trained in just one, maybe two scientific language games often feels overwhelming and can also be risky from a publication perspective. The world of scientific journals is mainly organized in clearly defined and often very narrow siloes. Transdisciplinary papers struggle to find a home in a top journal.

A holistic approach to measuring impact

The above-mentioned challenges make it difficult to reorient research toward Grand Challenges. This, however, is not the only problem in the relationship between scientists and society.

The problem of over-focusing on citations leads to profound inefficiencies for society in a critical period. The constant pressure put on scholars to publish prevents them from investing time in activities other than purely scientific research. Even teaching often pays this cost despite being absolutely essential. Peers might even think negatively of their colleagues if they spend too much time on other activities (teaching, communication, etc.) as it represents potential missed opportunities to publish more.

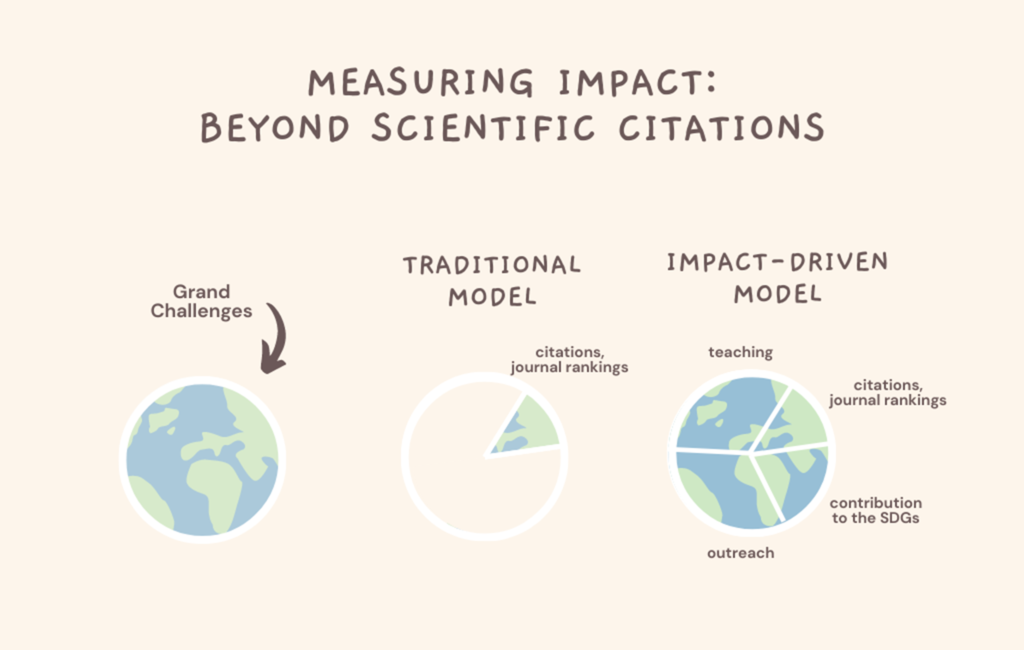

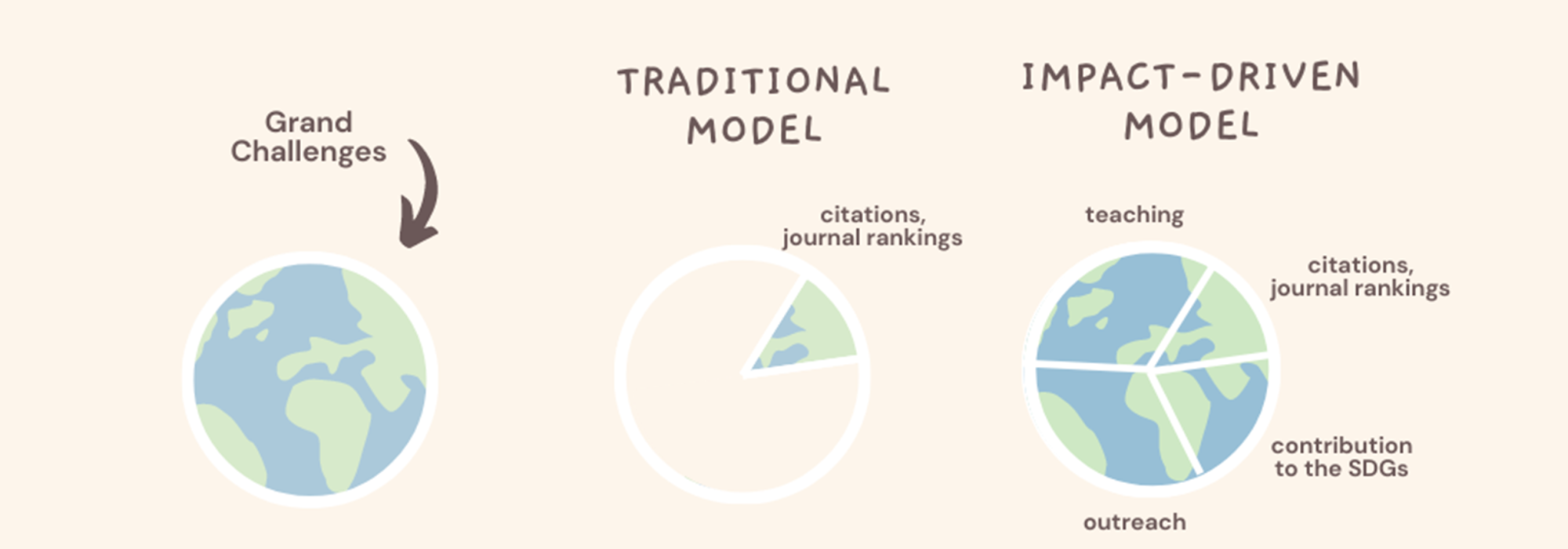

To tackle this issue we suggest two main changes. First, we must go beyond citations to assess the job done by researchers and take into account the importance of the findings for society, as well as giving significantly more weight to outreach activities and teaching (cf. Figure above). Second, we should allow and encourage diverse profiles for academic positions. Each researcher would invest more or less time in different activities (research, outreach, and teaching) allowing each department in academic institutions to be strong on the three levels mentioned by aggregating the multiple strengths within.

A. Alternative and richer metrics to measure impact

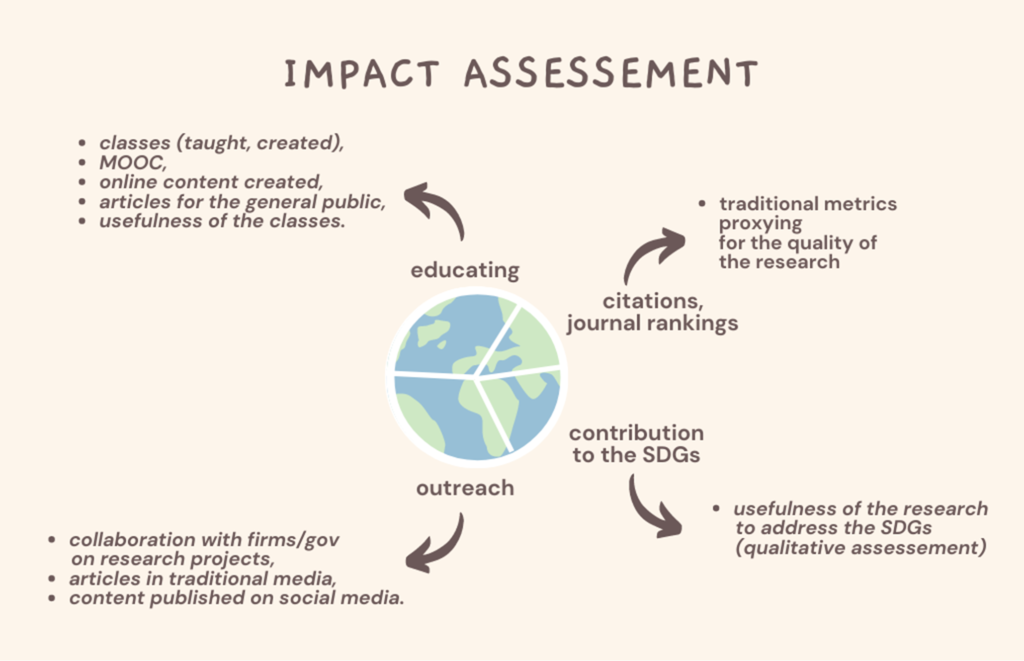

The current metrics used in academia remain useful proxies to assess the quality of the research. First, the number of citations is a relevant proxy for the impact on research per se. Second, journal ranking where the articles are published is also a good measure of the technical quality of the research. However, as discussed earlier these metrics are quite limited and problematic and hence should represent only part of a larger set of metrics with equal importance.

In addition to citations and journal names, the usefulness of the research results outside academia should be assessed as well. Qualitative evaluation could for instance identify how much the results help us reach the SDGs (Sustainable Development Goals).

Key results that remain within the walls of academia might have hardly any impact. Hence, it is necessary to also promote and evaluate outreach activities. Outreach activities include any activity outside academia aiming to exchange with policy-makers, firms, NGOs, or anyone directly concerned with the output. In addition, interventions in both traditional and social media, could be evaluated and encouraged as it enhance the reach of research and educational content.

Finally, teaching activities should be seriously taken into account. One of the main purposes of academia is to educate and share knowledge, yet who gets hired and promoted in academia doesn’t need to be a good teacher as long as they publish their work successfully. Education is key to fighting most of the main challenges we face today, from climate change to poverty, including discrimination. Hence, it is time to put education back as one of the driving forces of academia.

Reflecting on how to evaluate those criteria (research, outreach, and teaching) is essential to actively move forward with such an approach. Using quantitative metrics is mostly misleading and would poorly capture the quality of the work done. Hence, we suggest that applications for an academic position or grants, should emphasize the research impact on SDGs, and include an outreach statement (summary of past activities and the plan for future actions).

B. Diversified profiles

Realistically, asking academics to be top researchers, excellent teachers, and to invest time in the communication of science might be heroic. It is almost as unrealistic as training and evaluating academic staff exclusively on research criteria and then expecting them to teach well.

Therefore, we should allow for a diversity of profiles within each department. Some members might devote most of their energy to research, while others might dedicate a significant amount of time and energy to knowledge sharing or outreach activities. While we should indeed encourage other academics to engage in all these essential activities, freedom of specialization would be beneficial. This diversity should allow each department to have strong profiles on each dimension and hence produce an impactful output.

Conclusion: A new academic world

To think about disrupting the status quo, we must first understand it. Currently, university rankings focus extensively on citations. For example, citations and research represent 60% of the score of The Times Higher Education World University Rankings. Furthermore, grant evaluation committees often rely heavily on citations and journal rankings of published research by applicants to decide who will receive funding. In the current system money follows citations (grants/students) and hence universities over-rely on citations when they hire and evaluate scholars. The novel evaluation criteria we suggest would reward professors who have a greater impact on society.

Good old Karl Popper knew it already: Scientists have a moral duty to engage in democracy. However, he still assumed that science must be value-free and the scientists had to separate their engagement from their role as a scholar and express it in their other role as citizens. The current crisis makes this separation of research and engagement, of facts and values, impossible and it forces us to pause and reflect on what we do and how we define our responsibility and value our different activities. Ultimately, the question of what kind of world we want to live in is always also a normative one and it is hopelessly entangled with the knowledge we produce. As scientists, we either contribute to a stabilization of the current order of things or we drive the change.

Additional Information on the authors

Quentin Gallea:

I am a researcher, lecturer, and consultant passionate (obsessed) with causality.

I am committed to bridging academia and civil society through innovative teaching and research.

My passion drives me to:

- Work on how to prevent manipulation and bias (causal, cognitive, behavioral) with ESG KPIs in order to support the road to fight climate change.

- Spread knowledge in statistics to empower people allowing them to fight misinformation and make more educated decisions (seminars/classes/keynote, TEDx, daily content on LinkedIn, YouTube channel, Medium (Towards Data Science) publications, Instagram/TikTok page (@stats_with_quentin), etc.)

You can find all my content here: https://linktr.ee/stats_with_quentin

Guido Palazzo:

Guido Palazzo is a professor of Business Ethics at the University of Lausanne. He studied business administration and has a PhD in philosophy from the University of Marburg in Germany. In his research, he is passionate about the dark side of the force and examines unethical decision making from various angles. He is mainly known for his studies in globalization, in particular on human rights violations in global value chains, but he also studies the reasons for unethical behaviour in organization and the impact of organized crime on business and society.

-

Guido Palazzo

Guido Palazzo is a professor of business ethics at the University of Lausanne.

View all posts -

One Response

Good article. Academic scholars also need to think of ways to reach a wider audience. Most of the academic content, particularly research articles, is inaccessible, so no matter how impactful it is, it doesn’t reach the targets.